What Melted the Ancient Egyptian Statues of Tanis? Exploring the Role of Greek Fire

The mystery surrounding the scorched and seemingly melted statues of Tanis, an ancient city in Egypt’s Nile Delta, has captivated historians and archaeologists alike. Among the various theories proposed to explain this peculiar phenomenon, one intriguing hypothesis suggests the use of Greek Fire—a Byzantine incendiary weapon—as the cause of the damage. While speculative, this theory aligns with historical accounts of warfare, providing a possible explanation for the statues’ unusual appearance.

The Enigma of Greek Fire

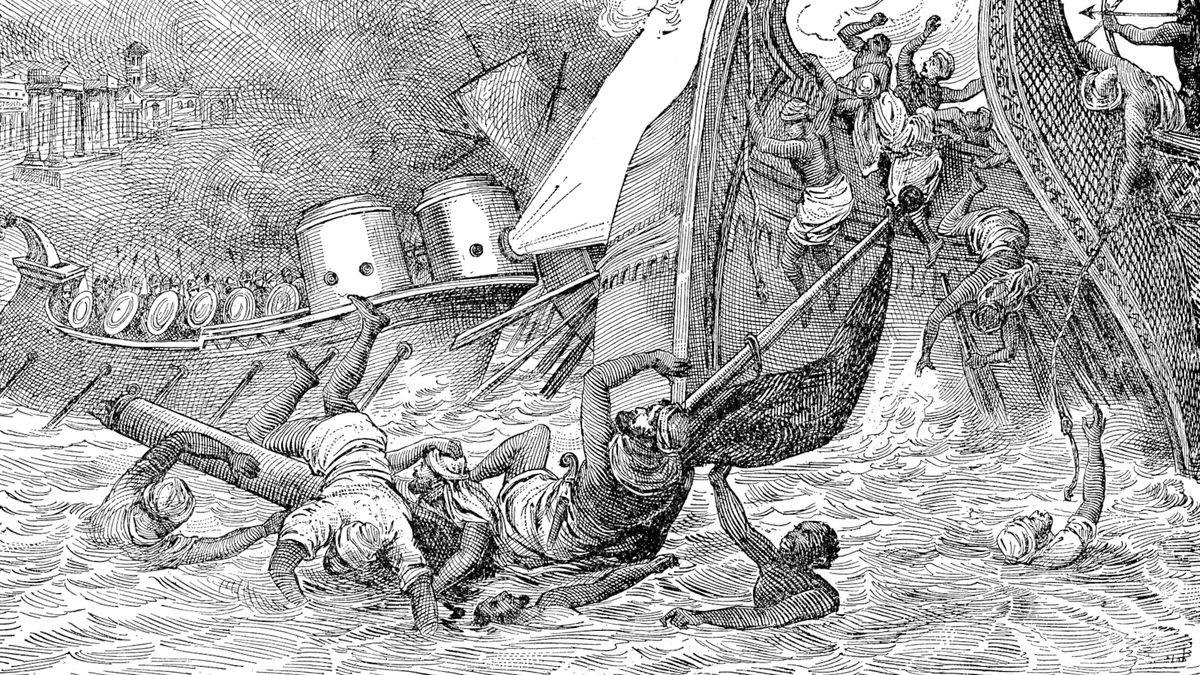

Greek Fire, developed by the Byzantine Empire during the 7th century AD, was a revolutionary weapon that granted a significant advantage in both naval and land battles. Also known as Sea Fire, Roman Fire, Liquid Fire, or Sticky Fire, it was infamous for its intense heat, reportedly exceeding 1,000 degrees Celsius, and its ability to burn even on water. This deadly concoction was a closely guarded secret, with its precise formula lost to history after the 12th century.

Contemporary accounts and Byzantine military manuals describe Greek Fire as being deployed through specialized siphons mounted on ships or siege engines, as well as in handheld devices akin to modern flamethrowers. The flames were said to adhere to surfaces, making them nearly impossible to extinguish. Historical records attribute its creation to a chemist named Callinicus of Heliopolis, although earlier uses of similar fire-based weapons in antiquity complicate the narrative.

Tanis: A City of Mystery

Tanis, a prominent city during the 21st Dynasty of Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period, has long been a site of fascination due to its monumental statues and ruins. Many of these statues, crafted from basalt and granite, display peculiar scorch marks and localized melting. This has led to debates about whether the damage was caused by natural phenomena such as earthquakes and subsequent fires or by human activity involving advanced incendiary technologies.

In the Byzantine period, Egypt endured considerable turbulence, including conflicts with the Persian Sassanian Empire and later invasions during the Crusades. Tanis, though primarily known for its earlier significance, might have been affected during these tumultuous times, possibly serving as a battleground.

Connecting Greek Fire to Tanis

The theory linking Greek Fire to the scorched statues of Tanis arises from several key observations:

-

Heat Damage and Material Composition: Basalt and granite, the primary materials used for the statues, melt at temperatures between 984–1260 degrees Celsius. The intense heat generated by Greek Fire aligns with the levels required to cause partial melting or discoloration of these rocks. This suggests that an incendiary weapon, such as Greek Fire, could be responsible for the observed damage.

Historical Context of Conflict: During the Byzantine period, Egypt was a contested region. The Persian invasion in the 7th century AD brought widespread destruction, including massacres and sieges. The Byzantines’ eventual recapture of the region may have involved the use of Greek Fire, especially in strategic locations like Tanis.

The Crusades and Fire Weapons: Later, during the 12th century AD, the Crusaders, possibly in alliance with the Byzantines, launched campaigns in Egypt. Historical accounts indicate the use of incendiary weapons, including flammable mixtures like naphtha. Given the Byzantine expertise in fire-based weaponry, it is conceivable that remnants of Greek Fire technology were employed during these campaigns, potentially affecting Tanis.

Localized Damage Patterns: The burn marks and partial melting observed on the Tanis statues appear to be localized rather than uniform. This suggests a targeted application of heat, consistent with the characteristics of Greek Fire, which could be directed at specific areas using siphons or other delivery mechanisms.

Alternative Explanations

While the Greek Fire hypothesis is compelling, alternative explanations cannot be discounted. For example, natural disasters such as earthquakes, followed by fires ignited by oil lamps or other flammable materials, could account for the damage. Additionally, prolonged exposure to intense heat from desert wildfires or lightning strikes might have contributed to the statues’ current condition.

Another possibility involves the deliberate defacement of statues during periods of political or religious upheaval. The use of conventional fire-based tools or other destructive methods might have produced effects resembling those attributed to Greek Fire.

Challenges to the Theory

Despite its allure, the Greek Fire hypothesis faces several challenges:

Lack of Direct Evidence: No definitive traces of Greek Fire or its delivery mechanisms have been discovered at Tanis. Without physical evidence, the connection remains speculative.

Chronological Gaps: The statues of Tanis date to much earlier periods, raising questions about whether they were even present during the Byzantine or Crusader eras. If they were already buried or damaged, their exposure to Greek Fire would be unlikely.

Technological Uncertainty: The precise nature and capabilities of Greek Fire remain uncertain due to the loss of its original formula. Modern reconstructions rely on speculation, making it difficult to assess its potential impact on the statues.

Conclusion

The burnt and melted statues of Tanis continue to intrigue researchers, offering a tantalizing glimpse into the mysteries of ancient history. The hypothesis that Greek Fire was responsible for their condition highlights the interplay between historical events and archaeological evidence. While the theory aligns with certain aspects of Byzantine and Crusader history, further investigation is needed to substantiate these claims.

For now, the enigmatic damage to the statues serves as a reminder of the complex and often violent interactions between civilizations. Whether caused by Greek Fire or other means, the scars on Tanis’ ancient monuments tell a story of resilience, conflict, and the enduring quest to understand the past.