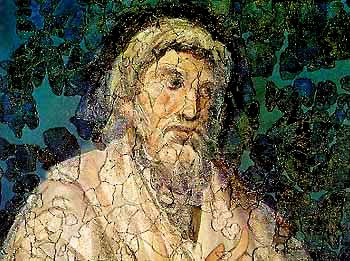

How Christianity Almost Vanished in 303 AD: The Great Persecution of Diocletian

In the year 303 AD, Emperor Diocletian launched a sweeping campaign to eradicate Christianity, marking the beginning of what would become known as the Great Persecution. On February 23, Diocletian issued an edict proclaiming the destruction of Christianity within the Roman Empire. Churches were to be demolished, sacred texts burned, and Christians of rank stripped of their status. Freed Christians could be re-enslaved, while those refusing to renounce their faith faced imprisonment, torture, or execution. This systematic persecution was the most intense and widespread attack on Christians in Roman history and posed an existential threat to the faith.

The Origins of the Persecution

Diocletian, a staunch defender of Roman tradition, believed the unity and stability of the empire depended on its adherence to the worship of the old gods. For Romans, religion was deeply intertwined with statecraft. The emperor himself held the title Pontifex Maximus—chief priest of the state religion—and was considered divinely chosen by the gods.

The Christians, with their monotheistic beliefs and rejection of pagan rituals, were seen as a threat to the social and religious fabric of the empire. Their refusal to participate in sacrifices and public festivals honoring the gods was viewed as antisocial and, worse, treasonous.

Diocletian’s policies reflected a broader pattern of suppression of what he saw as “barbaric” or disruptive beliefs. In 295, he banned the practice of sibling marriage, common in Egypt, as “fit only for barbarians.” In 302, he ordered the extermination of the Manichaeans, a dualistic religious group, burning their leaders alive and condemning their followers to execution or forced labor. This set the stage for the assault on Christianity.

Decius and the Precedent for Persecution

Although sporadic anti-Christian violence had occurred earlier, it was Emperor Decius in the mid-third century who first launched a systematic persecution. In 250 AD, Decius issued an edict requiring all citizens of the empire to perform sacrifices to the gods for the safety of the state. Christians who refused were arrested, exiled, or executed.

The Decian persecution demonstrated the imperial state’s willingness to enforce religious conformity. For Diocletian, these earlier measures provided a template for his own far-reaching campaign against Christians.

The Great Persecution Begins

Diocletian’s Great Persecution formally began with the proclamation of his edict on the Roman festival of Terminalia in 303 AD. Diocletian was reportedly hesitant at first, but pressure from his co-emperor Galerius and confirmation from the oracle of Apollo convinced him to act.

The edict ordered the destruction of Christian churches and sacred texts and prohibited Christian worship. The campaign began in Diocletian’s capital, Nicomedia, where the great church was razed to the ground.

In the empire’s eastern provinces, under Diocletian and Galerius’ direct control, enforcement of the edict was particularly brutal. Christian clergy were rounded up, imprisoned, and tortured to force them to renounce their faith. Those who refused were executed. By contrast, enforcement was much laxer in the western provinces, where Constantius Chlorus, father of Constantine the Great, was reluctant to carry out the edicts.

Intensification Under Galerius

Diocletian abdicated in 305 AD, leaving Galerius in charge of the empire’s eastern territories. Under Galerius, the persecution intensified. A second edict ordered all citizens to sacrifice to the traditional gods. Public sacrifices became mandatory, and failure to comply was punishable by death.

In 309 AD, Maximinus, Galerius’ nephew and successor in the eastern provinces, introduced even more draconian measures. Food in markets was sprinkled with sacrificial blood, making it impossible for Christians to purchase it without violating their faith. Public baths were similarly contaminated.

Despite these efforts, the persecution began to lose momentum. Public sympathy for Christians grew, especially as stories of their courage and suffering spread. In some cities, officials moved executions to the countryside to avoid unrest.

The End of the Persecution

The Great Persecution finally ended in 311 AD when a dying Galerius issued an edict of toleration. Acknowledging the failure of his efforts to suppress Christianity, he permitted Christians to worship freely, provided they did not disturb public order. Galerius even asked Christians to pray for his health, a remarkable reversal given his earlier hostility.

In 313 AD, the Edict of Milan, issued by Constantine and Licinius, formally legalized Christianity throughout the empire. The Great Persecution was over, but its consequences would shape the future of the Christian faith and the Roman Empire.

Consequences of the Great Persecution

The Great Persecution failed to destroy Christianity, but it left lasting scars. Many Christians were martyred, while others were tortured, enslaved, or exiled. The unity of the Christian community was tested, especially in North Africa, where debates over how to treat those who had renounced their faith during the persecution led to lasting schisms, such as the Donatist controversy.

Paradoxically, the persecution strengthened Christianity in the long run. Stories of martyrdom inspired faith and solidarity among believers. Exiled Christians founded monasteries in the Egyptian desert, laying the foundation for Christian monasticism.

The era also marked a turning point for the Roman Empire. Diocletian’s attempt to unify the empire through religious conformity foreshadowed Constantine’s later efforts to use Christianity as a unifying force. By the end of the fourth century, Christianity would replace traditional Roman religion as the empire’s dominant faith.

Legacy

Today, the Great Persecution is remembered as one of the most significant events in early Christian history. The martyrs of this era are venerated as heroes of the faith, and their legacy endures in the liturgies and calendars of churches like the Coptic Orthodox Church, which still uses the “Era of the Martyrs,” dating all events from the accession of Diocletian in 284 AD.

While Diocletian sought to extinguish Christianity, his actions inadvertently helped to strengthen and define it, ensuring its survival and eventual triumph as the dominant religion of the Roman Empire.