The Discovery of the “Tomb of Osiris” in Egypt: A Misidentified Marvel

On January 1, 1898, Émile Amélineau, a French Egyptologist, embarked on an excavation that would leave a significant mark on Egyptology. This site, near Abydos, was destined to fuel fascination, disappointment, and intrigue, as Amélineau announced he had found the legendary “Tomb of Osiris.” However, what seemed like a monumental discovery later became a source of skepticism and contention, as it was eventually realized that Amélineau’s interpretation was flawed. The site would become central to the study of Egyptian history, myth, and ritual, even if its mysteries unraveled differently than initially believed.

The Excavation Begins: A Site of Promise

Amélineau, born in 1850, entered Egyptology after studying for the French Catholic Church and developing an expertise in the Coptic language and the Christian history of Egypt. Securing a five-year exclusive contract with the Egyptian Antiquities Service, Amélineau began working at Abydos, a location revered in ancient Egyptian tradition as the final resting place of Osiris. Knowledge of ancient Egypt was still expanding, and the allure of locating a tomb associated with the god Osiris would not only fulfill a scholarly dream but also offer a profound historical and cultural revelation.

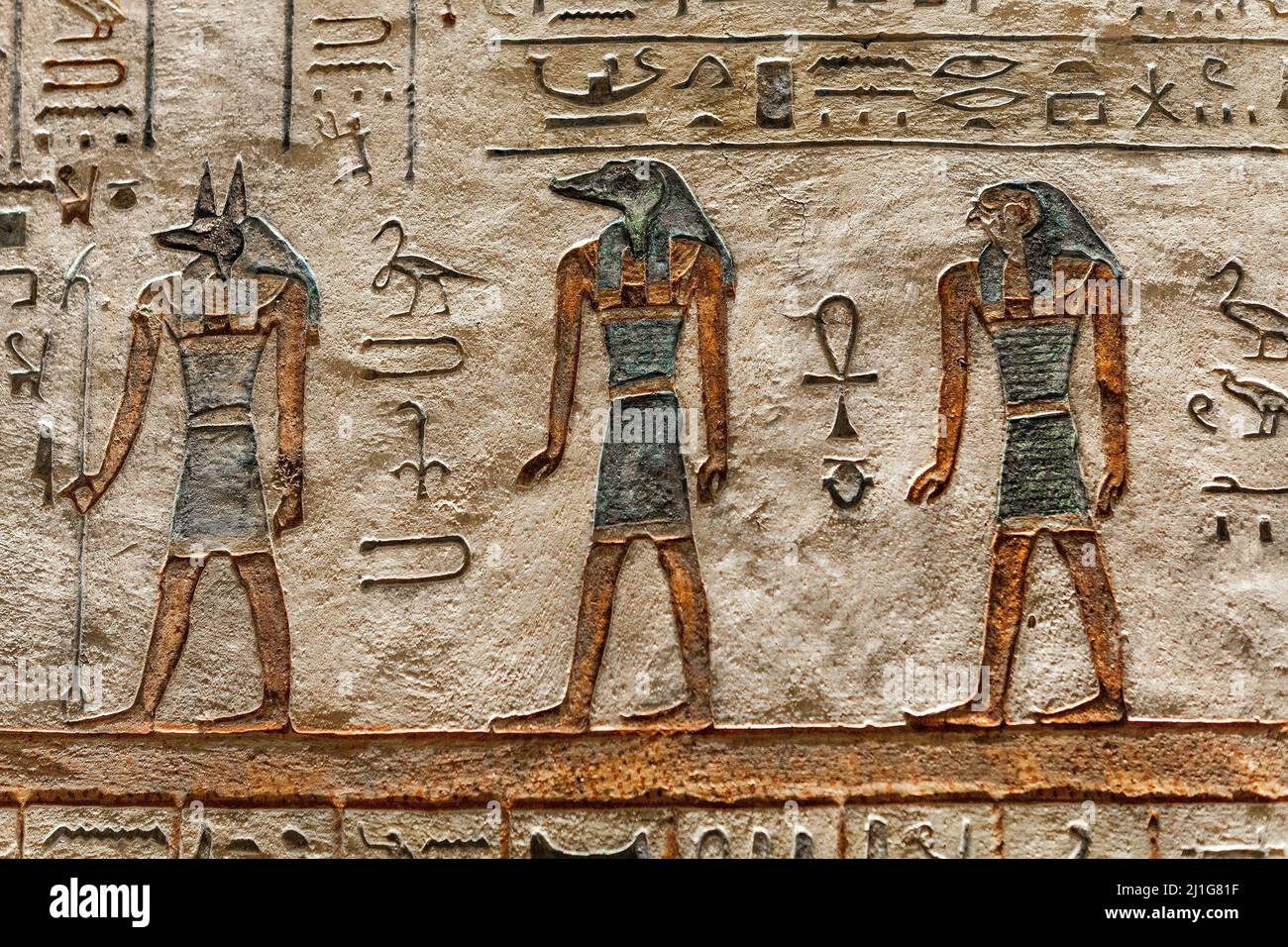

In the early days of the excavation, Amélineau’s team discovered a grand necropolis containing a wealth of artifacts that seemed to align with Osirian symbolism. The most significant find was a large basalt structure intricately carved to depict Osiris lying on his back, wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt, surrounded by symbols of Horus and Isis. Given these elements, Amélineau believed he had stumbled upon the physical tomb of Osiris himself, sparking excitement among enthusiasts and scholars alike.

A Monument Misinterpreted

The excavation, however, was marred by hasty and incomplete methods. Amélineau reportedly overlooked or discarded many artifacts, keeping only those that were intact and ignoring fragmented but historically valuable items. His approach led to the loss of invaluable context and, as later discovered, resulted in significant misinterpretations of the artifacts’ origins and meaning.

The basalt sculpture, which Amélineau took to be the sarcophagus of Osiris, lay on its side and bore details aligning with Osirian iconography, such as a lion-shaped base and falcons symbolizing Horus. Yet, these artifacts were not enough evidence to declare this the god’s tomb. In a nearby chamber, Amélineau discovered a human skull, which he attributed to Osiris, though further analysis later revealed it was the skull of a woman. Despite this discrepancy, Amélineau maintained his conviction that he had found the god’s tomb, publishing his findings in 1899. This publication, while lengthy and filled with detailed descriptions, was met with skepticism from the archaeological community.

A New Analysis: Flinders Petrie’s Intervention

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, a prominent British Egyptologist, was particularly skeptical of Amélineau’s claims. Petrie, whose methods were meticulous and systematic, obtained permission to revisit the site after Amélineau’s excavation contract was terminated in 1899. His re-excavation unveiled artifacts and details that Amélineau had overlooked or disregarded, including a human arm adorned with gold and turquoise jewelry. These discoveries contradicted Amélineau’s interpretation of the site as the “Tomb of Osiris.”

Upon further examination, Petrie determined that the tomb likely belonged not to Osiris, but to a pharaoh named Djer, the third king of Egypt’s First Dynasty. The so-called “Tomb of Horus and Set” that Amélineau had identified was later found to be associated with a different ruler, Khasekhemwy, from the Second Dynasty. Petrie’s work revealed a clearer understanding of the site’s early dynastic significance, and he published comprehensive accounts that corrected Amélineau’s initial assertions.

A Shrine Dedicated to Osiris

Despite the site’s association with Djer, Amélineau’s belief that it held religious significance was not entirely unfounded. Centuries after Djer’s time, during the Middle Kingdom, Egyptians revered the tomb as a place of pilgrimage, believing it to be associated with Osiris. This transformation into a ritual site was an early example of how religious narratives shaped ancient Egypt’s historical interpretation.

In this period, the tomb of Djer was modified to serve as a shrine for Osiris, attracting worshippers from across Egypt. Rituals were performed in dedication to Osiris, and the site gained renown as a destination for pilgrimage. Pilgrims from distant regions sought proximity to the tomb, building stelae and other markers to denote their presence. The basalt “Osiris Bed” sculpture, which had confounded Amélineau, was later analyzed and identified as a product of the 13th Dynasty, far removed from the timeline of Djer and Osiris’s original mythological narratives.

The Continued Reverence of the “Tomb of Osiris”

The tradition of honoring this site as the tomb of Osiris persisted into later periods of Egyptian history, including the Second Intermediate Period. A 13th Dynasty king, Djedkheperew, left his name inscribed on a section of the basalt monument, signifying the political and spiritual endorsement of the site’s Osirian association. This legacy continued until the Persian invasion in 525 BCE, though some evidence suggests that offerings were still occasionally left there even during the Roman era. This long-lasting reverence for the tomb underscores the significance of myth and ritual in shaping historical legacies.

Legacy of the Discovery

Although Amélineau’s initial identification of the site as the “Tomb of Osiris” was erroneous, his findings nonetheless illuminated aspects of Egypt’s religious practices and the early dynastic period. His efforts, albeit flawed, initiated further inquiry, ultimately leading to Petrie’s more rigorous and accurate interpretations. Today, the site is recognized not as the literal tomb of Osiris, but as a remarkable intersection of early dynastic and religious significance, where historical rulers and mythological figures were memorialized in the hearts and minds of ancient Egyptians.

Amélineau’s claim to fame rests on an ambitious but mistaken hypothesis; he may have been driven by the allure of uncovering the divine or by a desire for recognition. Nevertheless, his work brought attention to a location of profound importance in Egyptian tradition. His initial excitement, though, serves as a reminder of the need for careful archaeological practice, an aspect Petrie’s later work underscored. As historians and Egyptologists continue to explore and reinterpret ancient Egypt’s ruins, the story of Amélineau’s “discovery” remains an essential chapter in understanding the interplay between myth, history, and archaeology.

Conclusion

The tale of the so-called “Tomb of Osiris” highlights both the fervor and fallibility of early archaeology. Amélineau’s journey to Abydos led him to an ancient, revered tomb, yet his initial misinterpretations clouded the true nature of his find. It was Petrie’s meticulous analysis that revealed the site’s real connection to Egypt’s First Dynasty and clarified its role in the mythic and ritualistic tapestry of ancient Egyptian culture. The transformation of Djer’s tomb into a Middle Kingdom shrine dedicated to Osiris demonstrates how mythology can reshape historical sites, endowing them with meanings that endure across centuries. This story of rediscovery serves as a fascinating lesson in archaeology, illustrating how scientific rigor can illuminate the past even when clouded by myths and misconceptions.